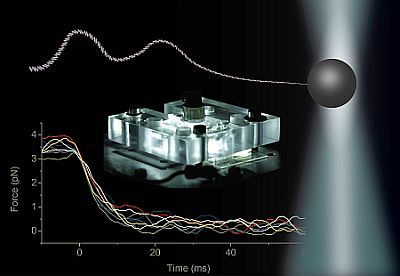

Focus 1: Controlling molecular transport through nanopores

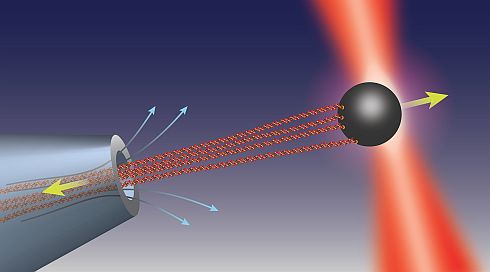

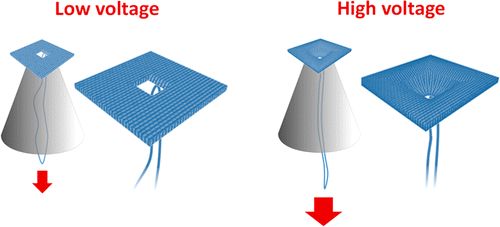

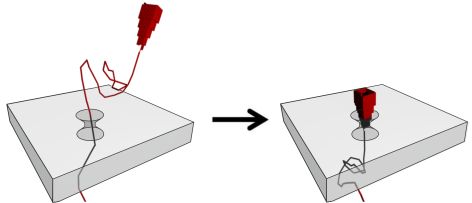

We study the forces that govern the transport of DNA and other molecules through nanopores. Our experimental efforts combine optical tweezers, fluorescence sensing and electrophysiology (ionic current sensing). Our aim is to gain novel insights and translate our findings into nanopore systems with enhanced sensing capabilities. We want to enhance the specificity, sensitivity and durability of nanopore sensors. Our nanopore systems are made out of glass nanopores, nanopores in thin silicon-based membranes, and in sheets of graphene and hBN.

Involved researchers:

Casey, Filip, Jinbo, Kaikai, Mohammed, Sarah

Collaborators:

Sandip Ghosal (Northwestern University), Murugappan Muthukumar (University of Massachusetts, Amherst)

Key references:

K. Chen, I. Jou, N. Ermann, M. Muthukumar, U. F. Keyser, and N. A. W. Bell.Nature Physics, 17(9):1043-1049, 2021. [ DOI | http ]

N. A. W. Bell and U. F. Keyser. Nature Nanotechnology, 11:645-651, 2016.[ DOI | .html ]

U. F. Keyser. J. R. Soc. Interface, 8:1369-1378, 2011. [ DOI | http ]

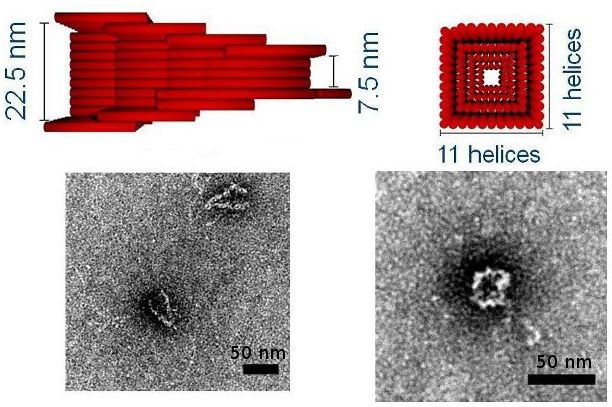

Focus 2: Building with RNA and DNA

We are using DNA self-assembly for building of functional nanostructures. Since our demonstration of DNA origami nanopores we have been imrpoving our fundamental understanding of artificial membrane nanopores.Now, we are using DNA and RNA scaffolded structures to enhance sinle-molecule sensing. Especially the identification of RNA molecules is a current focus. In parallel, we are building plasmonic nanostructures through a close collaboration with Jeremy Baumberg's lab in the Nanophotonics Centre here in Cambridge.

We also use DNA for data storage application and are developing techniques for data writing and reading into DNA using self-assembly by hybridization. Over the last years we have shown that our nucleic acid nanostructures can be used for data storage. DNA nanotechnology allows dynamic changes of the data without the use of enzymes which we call DNA hard drives. We are actively developing this area in combination with the techniques in the microfluidic epxertise of the KeyserLab.

Videos:

DNA origami explanation

Involved researchers:

Casey, Gerardo, Kevin, Max, Robert, SaraR, Thieme

Collaborators:

Aleksei Aksimentiev (Urbana-Champaign), Philip Tinnefeld (LMU, Munich), Tim Liedl (LMU, Munich), Fernando Moreno-Herrero (CSIC Madrid), Oxford Nanopore Technologies

Key references:

F. Bošković and U. F. Keyser. Nature Chemistry, published online, 2022. [ DOI | http ]

K. Chen, et al. Nano Letters, 5(5):3754-3760, 2020. [ DOI | http ]

K. Göpfrich, et al. Nano Letters, 16(7):4665-4669, 2016. [ DOI |http ]

N. A. W. Bell, et al. Nano Letters, 12(1):512-517, 2012. [ DOI | http ]

Reviews:

S. M. Hernandez-Ainsa, , and U. F. Keyser. Nanoscale, 6:14121-14132, 2014. [ DOI | http

N. A. W. Bell and U. F. Keyser. FEBS Letters, 588(29):3564-3570, 2014. [ DOI | http ]

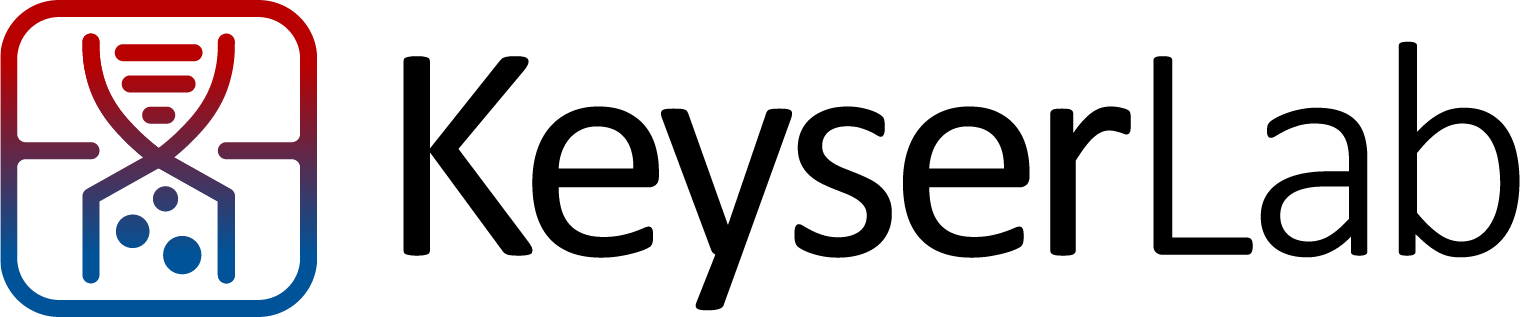

Focus 3: (Drug) Transport through lipid membranes

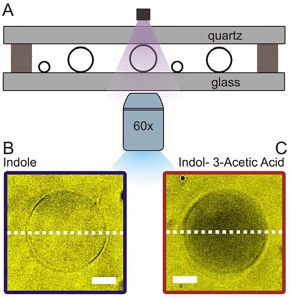

Passive membrane transport is ubiquitous in living organism. One class of special interest are small organic compounds like indole. In many respects indole behaves like the signalling component of a quorum sensing system. Indole synthesised within the producer bacterium is exported into the surroundings where its accumulation is detected by sensitive cells. By direct observation of indole import into individual liposomes we have shown that indole can cross a lipid membrane without the aid of a proteinaceous transporter and provide a simple explanation for the ability of indole to signal between biological Kingdoms.

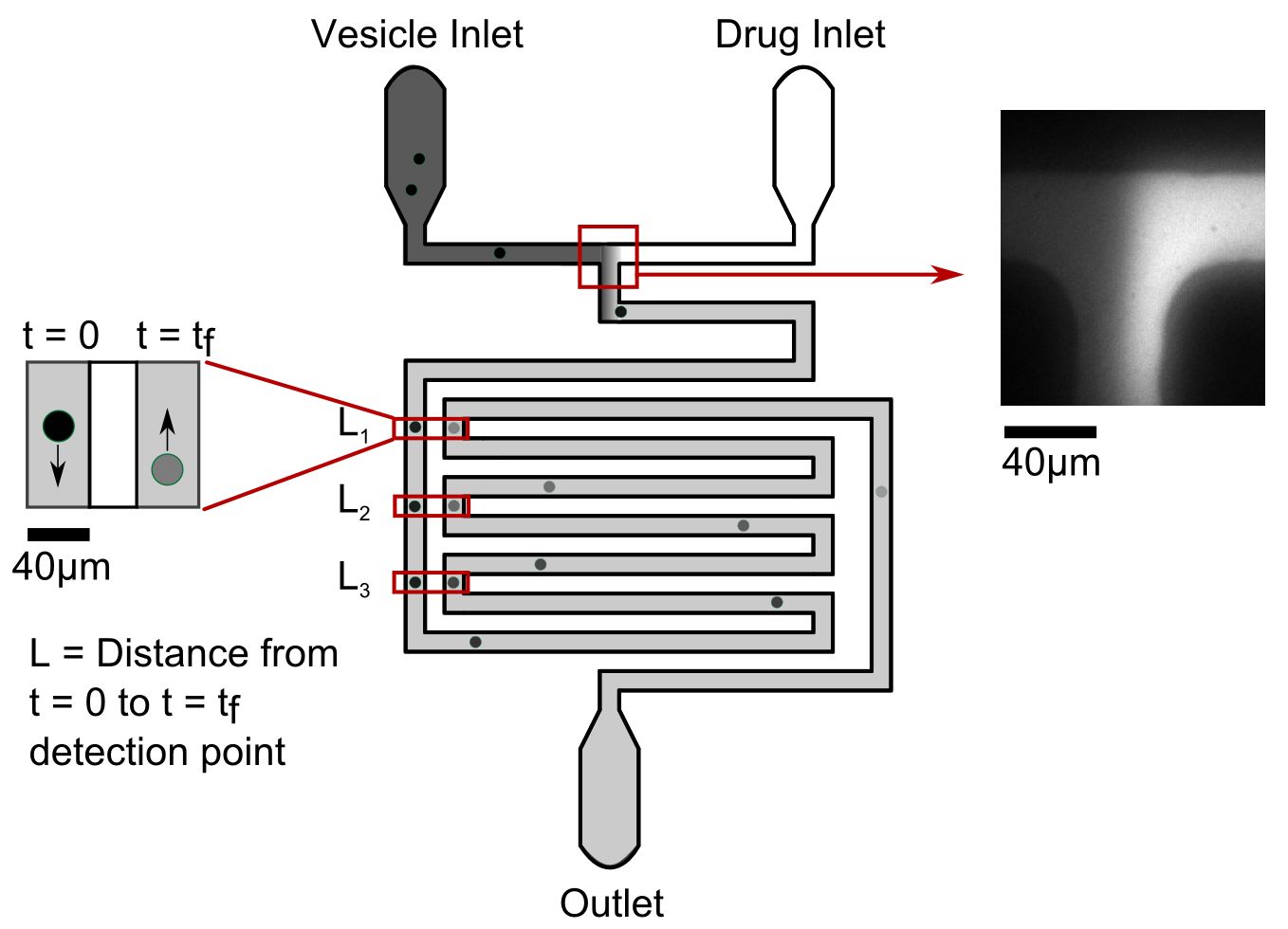

Our microfluidic technique enables quantification of drug transport through lipid membranes. Since passive transport accounts for over 80% of drug uptake in cells it has special relevance for the understanding of antibiotic resistance. Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) are used as model membranes; the lipid composition of these membranes is fully controlled. Our optofluidic assay directly measures the Permeability Coefficient of a drug crossing lipid membranes. We are able to screen the permeability properties of various autofluorescent drugs in a lipid specific manner, without needing to resort to octanol partition coefficient measurements. Furthermore, we can study the effect of membrane proteins on drug transport. We are now using our system to quantify drug transport in highly controlled environments with special emphasis on clarifying the role of outer membrane channels in antibiotics resistance.

Involved researchers:

Jehangir, Marcus, Ran

Collaborators:

Tuomas Knowles (Chemistry), Max Ryadnov (NPL), Stefano Pagliara (Exeter), Mathias Winterhalter (JU Bremen), David Summers (Genetics, Cambridge), Fiona Gribble and Frank Reimann (Institute for Medical Research, Cambridge)

Key references:

M. Schaich, et al. Mol. Pharmaceutics, 16(6):2494-2501, 2019. [ DOI |

http ]

K. Al Nahas, et al.

J. Cama, et al. JACS, 137(43):13836-13843, 2015. [ DOI | http ]

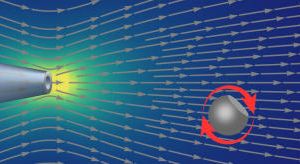

Past focus: Physics of Channels

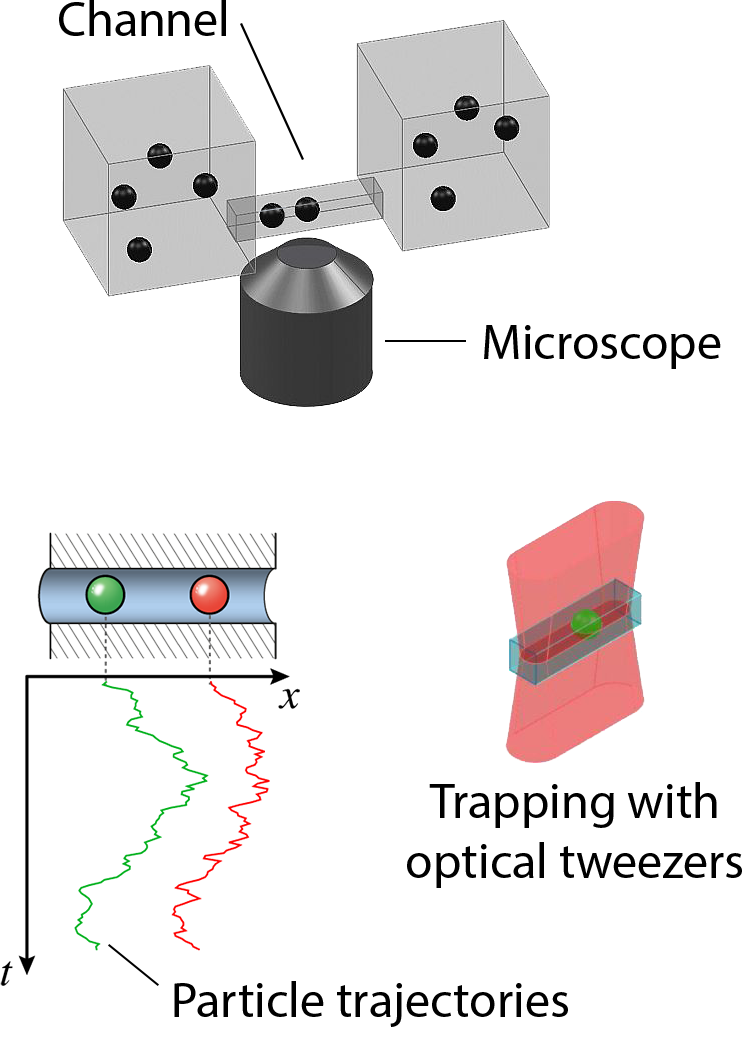

Transport of ions, metabolite molecules and macromolecular solutes across biological membranes is an ubiquitous process in nature. Specifically membrane proteins form metabolite-specific channels with large aqueous pores exhibiting affinities to their metabolites. To understand the physics of molecular transport, we have developed a microfluidic model system that mimics protein membrane channels. This setup allows us to record trajectories of each particle, which are then used to characterise the Brownian motion, particle-channel interactions and particle-particle interactions. In addition, we mimic facilitated transport by creating synthetic binding sites with holographic optical tweezers. This offers a unique method for controlling the potential landscapes within the channels. Ultimately, we aim to understand how the channel-shape and -potential controls transport through them. Recently we characterised a novel mode of hydrodynamic interactions in narrow channels that mediate non-decaying interactions. We are now looking into systems where the particles diffuse in complex potential landscapes and are driven by externa forces.Involved researchers:

Stuart

In collaboration with:

Douwe Bonthuis (Graz), Stefano Pagliara (Exeter), Eric Lauga (DAMTP), Sergey Bezrukov (NIH, Bethesda), Miguel Rubi (Barcelona)

Key references:

K. Misiunas and U. F. Keyser. Phys. Rev. Lett., 122:214501, 2019. [ DOI | http ]

S. Tottori, K. Misiunas, U. F. Keyser, and D. J. Bonthuis. Phys. Rev. Lett., 123:014502, 2019. [ DOI | http ]

K. Misiunas, et al. Physical Review Letters, 115:038301, 2015. [ DOI |

S. Pagliara, S. L. Dettmer, and U. F. Keyser. Phys. Rev. Lett., 113:048102, 2014. [ DOI | http ]

Videos:

Non-decaying interactions - explained

Diffusing particles (4.5MB)

Tracking particles (2.8MB)